Pacific Islands

The Pacific is not just the world's largest ocean, it is host to numerous islands with a rich diversity of culture and languages, reefs and atolls, mountains and forests, flora and fauna. These 22 unique island countries and territories are home to more than 7 million people, and their uniqueness makes them one of the most vulnerable regions in the world facing the impacts of climate change. From the highest of the volcanic islands to the lowest lying coral atolls, the entire region is under threat.

The especially fragile island ecosystems of the small island nations places them on the frontline in the battle against climate change, making them the litmus test for climate change impacts globally. Often referred to as people from the Small Islands, Pacific Islanders are in fact the people of the Large Oceans. They remain resilient in the face of climate change, making every effort to overcome the environmental, social and economic catastrophe that it brings and to adapt to survive and save their islands.

We are not just trying to save our islands, we are trying to save the entire world. If the Pacific islands disappear, then it will already be too late for everyone else.

Key Climate Risks and Adaptation

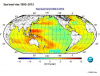

Over the past 20 years, the sea level in the Pacific Islands region has risen much faster than the global average.

The impacts of climate change in the Pacific are undeniable and have been confirmed by scientists and by Pacific Islanders who are already facing its consequences. The Pacific Islands are faced with risks posed by sea-level rise, cyclones, increase in air and sea surface temperatures, ocean acidity and changing rainfall patterns that affect their agriculture, geography, coral reefs, marine life, the health of their populations and ultimately their economies.

Already, the island countries have been subjected to destructive cyclones, loss of land from coastal inundation due to sea-level rise and storm surges, coastal flooding and coastal erosion, prolonged droughts and loss of coral reefs that have affected food security and left their coastlines unprotected and vulnerable. Impacts of pollution, over-population and over-exploitation of limited natural resources are exacerbated by climate change leading to a loss of biodiversity, land, and placing an even greater burden on future generations. Fiji, Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea have already had to relocate some communities to higher ground due to the impacts of climate change, while low-lying countries like Kiribati and Tuvalu are faced with the loss of their entire nations due to sea-level rise.

The impacts of rising sea levels

The sea is an intrinsic part of life in the Pacific Islands. Fisheries is a crucial sector: the sea translates into food security, livelihoods and a source of revenue for Pacific governments. It is their identity, their source of food, the mainstay of their economies; it protects them and yet has the potential to debilitate them.

Sea temperature rise and ocean acidification act as current and future climate-related drivers of risk, which further threaten fisheries along with overfishing and illegal commercial fishing that affect the livelihoods of the Pacific Island people. The combination of coral bleaching and ocean acidification is also harmful to coral reefs, the destruction of which will affect marine ecosystems and ultimately disrupt the food web. Projected sea level rise and warming sea surface temperatures will likely cause a decline in the productivity of fisheries in the tropical Pacific.

Changes in the movement of tuna stock, also a result of climate change, pose a geo-political risk as shifting stocks mean a shift in economic power. While greater effort is required to protect fisheries, in the Pacific countries have also adapted to the changing environment with greater cooperation amongst the islands.

Small Island Developing States are considered pioneers in setting up a fishery regime where the challenges they are faced with are used to promote cooperation with neighbouring island countries, a stellar example of this being the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA). PNA members, i.e. the Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu, oversee the world's largest sustainable tuna purse seine fishery (a fishing technique using a large seine) with first-time conservation measures such as protection for whale sharks, high seas closures to fishing etc.

Pacific Islanders have a rich history of migration, navigating their way across the Pacific in canoes and sailboats (the "ultimate green sea transport") and making the islands their home. As such they are also very resilient people, strengthened by their Pacific spirit of togetherness, religion, traditions, sense of community and strong connection to the land, sea and their people.

To many Pacific Islanders, traditional knowledge is a way of life and means of survival. Traditional knowledge is information and beliefs regarding the relationship of living things to one another and their surroundings. It is based on a deep understanding of the local environment. This knowledge has been passed down from generation to generation through stories, songs, poems, ceremonies and rituals. Traditional knowledge is unified and holistic. It originates from and is characteristic of a particular society and its culture. It further advances scientific understanding of climate change, offering new information about changes and impacts and providing new perspectives for adaptation.

Adaptation is key because the strongest mitigation efforts cannot avoid all impacts of climate change. By weaving traditional knowledge and science, Pacific Islanders are trying to adapt to the impacts of climate change. The adaptation process helps build adaptive capacity, reducing the islands' exposure and sensitivity as well as their vulnerability to climate change. Reducing vulnerability is the basis of adaptation. It is important that we collect and analyse information on exposure and sensitivity to climate stresses, projected climate impacts and adaptive capacity to better understand who is vulnerable and why. From this, appropriate actions and activities can be designed and implemented.

Some examples of adaptation actions and activities are:

- to establish early warning systems,

- grow resilient staple crops such as yams and taro,

- diversify crops grown,

- plant and maintain mangroves and native vegetation, and

- increase rainwater harvesting,

Pacific Islanders have persevered for hundreds of years to survive in their fragile ecosystems. Where adaptation in their current location may no longer be an option, migration helps communities find a new place to live and thrive, ensuring the sustainability of various peoples, cultures and their way of life in the Pacific.

Multifaceted mangroves

Along with their economic value, mangroves bear great cultural significance in the Pacific. They also serve as carbon sinks, storing carbon through living biomass and in their sediment deposits, comparable to rainforests in their ability to capture and store carbon from the atmosphere and thus support climate change mitigation.

A typical image of the Pacific is of low lying islands and coral atolls with sandy beaches. But some islands also boast tropical rainforests, wetlands and savannahs that are biodiversity hotspots. Large numbers of endemic species are under threat, demonstrating the range of impacts climate change can have on the region, which is host to a variety of ecosystems.

Unsustainable land use practices, deforestation, illegal logging, mining and invasive species all pose a threat to biodiversity in these islands, especially coral reefs, which are often called the rainforests of the sea and affecting agriculture and thereby endangering food security. These threats are further exacerbated by the impacts of climate change on the ecosystems. The already narrow natural resource base in the smaller islands is thus further diminished.

The loss of mangroves is also a threat to the Pacific as they are a means of coastal protection for the islands and a habitat for a variety of plant and animal species that support the food chain and livelihoods.

The sustainable development of our island countries relies on the health and vitality of the marine environment. For the Pacific SIDS, the 'green economy' is in fact a 'blue economy'.

Although the Pacific is one of the lowest contributors to global carbon emissions, it still takes the lead in setting an example with its mitigation efforts. Pacific Island countries have come together to set emission targets to make the region more sustainable and ensure energy security in the region with a move towards renewable energy sources. This comes in the form of national targets set by each country as well as regional efforts. For example, 13 Pacific Island Countries, Australia and New Zealand have signed the Majuro Declaration for Climate Leadership to collectively make a pledge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions urgently by setting specific targets and make a political commitment to become climate leaders in order to tackle climate change. Integrated water and energy policies will help maintain the intricate balance of the water - energy nexus in the Pacific. There is a need to support both by using hydro-dams and solar energy in order to limit further fossil fuel consumption and pollution.

These and other policies are captured by the concept of a Green Economy. According to the United Nations Environment Program, a green economy results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. It prioritises renewable energy, encouraging and developing the use of solar, wind, wave and geo-thermal energy and bio-gas while also promoting clean and sustainable transportation – both land-based and sustainable shipping – as well as better water, waste and natural resource management.

Small Island Developing States have refined this concept by what has been coined the Blue Economy. They consider their vast ocean as a means of sustainability: through harnessing waves for energy, wind for sustainable shipping, focusing on sustainable management of fisheries and the protection of marine biodiversity and fish stocks. The Blue Economy is based on the principles of promoting innovations inspired by nature that provide benefit to Pacific people without producing waste or depleting their resources. Pacific Islanders are leading the way in establishing Green and Blue Economies to provide climate and disaster resilience to their Large Ocean states.