Southern Africa

Southern Africa faces significant risks due to climate change. The region is already highly exposed to the effects of periodic warming of the Pacific or El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the cold episode of ENSO or La Niña. These cycles respectively cause severe droughts and floods in the region. They are a major driver of climate variability, which is partly responsible for food insecurity.

The frequency of extreme weather will increase with climate change. Since the early 1980s, the frequency and intensity of ENSO episodes has increased. Cyclones and storm power have increased in the past 30 years. Gradual warming has raised maximum temperatures resulting in heat stress. The increased frequency and intensity of climate events further impacts on the ability of communities, societies and economies to recover from shocks.

Parts of the region are already experiencing water scarcity. Increased drying, warming and extreme weather events will make this worse. Water scarcity (and in some cases water related disasters such as floods) have direct and indirect implications for food security, health and mobility of people, which in turn have implications for conflict potential.

Economic and human development is central to the Millenium Development Goals.

Risk and vulnerability, and capacity in southern Africa

Existing hotspots may extend over the next decades to the north-western parts of the southern African region, into southern and central Angola, and parts of southern and western DRC. This is due to low adaptive capacity in coping with climate change impacts in these areas.

The Regional Climate Change Programme however, identifies centres of resilience in the Congo Basin, Eastern Angola and the border between Tanzania and Mozambique. Stable and humid environments for instance, mean lower climate change impacts in the Congo Basin extending into Eastern Angola.

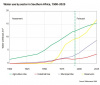

The map shown on the left highlights the areas where climate change stressors currently have the greatest impact on food security and, to some extent, health. The research is based on the best available geo-referenced data for 40 variables within three categories: adaptive capacity; environmental and nutritional sensitivity; and exposure to climate risk.

Red values indicate hotspots where people will most likely need help adapting to climate stressors, while the blue areas indicate lower sensitivity and exposure, and more resilience.

Across countries in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) there is wide variability in environmental and nutritional sensitivity, as well as level of vulnerability due to exposure to climate change impacts. A heavy reliance on dry-land farming, large rural population, low economic diversification and poor infrastructure exa≠cerbate the challenges and vulnerability. However, SADC countries also vary greatly in their capacity for adaptation to climate change. Adaptation planning should be as spatially explicit as possible and the Regional Climate Change Programme (RCCP) focuses on adaptation capacity and poverty reduction.

Exposure and vulnerability to climate change

Southern Africa is already experiencing rainfall variability and higher temperatures. Currently, the countries most at risk to climate stress are: Madagascar, Mozambique, Mauritius, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Botswana and parts of Namibia, Angola, Zambia and Swaziland. Thus, the greatest exposure to climate risk is broadly between 12°S and 25°S latitudinal band. The eastern seaboard of southern Africa and the island states are exposed to cyclones and floods. Arid and semi-arid regions in the west are prone to climate risk, mainly periodic droughts and the risk of flash floods. The northern Democratic Republic of the Congo, southern and south-eastern South Africa and part of south-east Tanzania, north-west Tanzania and the south-east corner of Madagascar are least exposed to climate risk.

The past and current experience of climate stress in southern Africa is unlikely to change drastically in the near future. Countries that have experienced the greatest number of droughts, floods and storms over the last century are likely to be exposed to the same events in the forthcoming four decades, although increases in exposure could emerge elsewhere too.

When vulnerability is considered, the arid and semi-arid regions exposed to periodic droughts fare better than the rest. South Africa, Botswana and Namibia form a major block of socio-economically stronger countries in the south-west: their infrastructure and more diversified economies give them a measure of resistance and resilience. Similarly, Mauritius also has a high adaptive capacity. Lesotho, Swaziland and Zimbabwe are intermediate while the DRC, Zambia, Mozambique and Madagascar, Tanzania and Malawi all have weaker socio-economic conditions and thus limited capacity to adapt to climate change impacts.

When the vulnerability aspects are projected to 2050, hotspots are evident in the high exposure and lower adaptive capacity areas in southern and central Angola, and parts of western DRC. Central eastern regions covering southern Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, southern and central Mozambique remain hotspots.

Water scarcity

There is increased recognition at a policy level of the potential threat to peace and security posed by water scarcity. The Africa Climate and Development Agenda Statement of the African Ministerial Council on Water (AMCOW) incorporates security risks into the region's approach to water and climate change. The SADC regional climate change responses factor in climate change impacts on regional human security.

Most of southern Africa's renewable water is found in shared transboundary river basins. In such cases, given the scarcitry of water in the region, the pursuit of individual national interests can act as a conflict threat. On the other hand, transboundary water resources management that builds on relationships can lead to inter-state cooperation.

Water is already scarce in the south-western regions of Botswana, Namibia and South Africa. Under climate change scenarios of reduced precipitation, these drier regions are likely to spread, ultimately including countries such as Zambia, Zimbabwe and southern Angola. Extreme dry events in the Kalahari could result in the eastward and northward encroachment of the Kalahari Desert. Even areas currently not suffering from water scarcity are at risk of per capita water scarcity, as future climate, population and development pressures result in greater demand for decreasing freshwater resources.

Water scarcity threatens security at various levels, human and political. Water-related human security issues manifest themselves through conflicts at individual and household levels, as well as intra- and inter-village levels. Household, intra- and inter-village conflicts happen when water resources are not adequate to meet the basic hygiene, drinking, food production and livestock watering needs. Human uses may also compete with livestock uses, and politically related conflicts may be amplified by water scarcity. For example, the Matabeleland region of Zimbabwe is regarded as a conflict flash point if water scarcity is not resolved.

Food insecurity

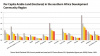

Climate change, in addition to increased water scarcity, will affect food security in southern Africa. Even without climate change, the regionís agriculture is failing to meet the food security needs of its citizens, and per capita food production has stagnated, with some countries experiencing reduced food production since the 1990s. This highlights the presence of additional factors or 'multiple stressors' to the food security situation in the region.

Climate change will thus act as an additional stressor on an already struggling sector. It will impact most of the millions who are dependent on rain-fed agriculture and ecosystems for their livelihoods. While food production relies on rural land, there is a history of mobility from the same areas to urban areas. Thus while growing populations are relying on purchasing food, income generation through jobs is suffering due to stagnation in economic growth. Increasing food prices over the last decade have also affected food security and human health, and the prospect of climate change and increased costs of food paint a bleak picture of food security in the region.

Climate change can result in 'shocks' that result in poor crop yields and failures. These will include floods during crop seasons, increased temperatures for which there is poor farming adaptation, and droughts. Storm surges are projected to increase along coastlines (notably in Mozambique) while the central parts of the sub-region are prone to drought cycles driven in part by ENSO. This has implications for rain-fed agriculture, which is the main source of food for the majority of people. It is estimated that the combined effect of precipitation changes and increased temperatures could likely result in 30% reduction in food production. These events are likely to persist and intensify under climate change with severe impacts for food security. Floods in Malawi in 2011 nearly wiped out entire crops, resulting in the residents turning to food aid for their survival.

Health

The impacts of extreme weather on vulnerable populations are well recognised. In southern Africa, extreme variations in the supply of water and poor water quality are connected to human health through multiple direct and indirect pathways. Water is thus the key climate change-health link. The potential for unexpected disease outbreaks and disruptive illnesses is water- and climate-related.

Poverty-led rural-to-urban migration leads to overcrowded peri-urban settlements where improved water supplies, sewage systems, roads and health services are lacking, and a high vulnerability to water-borne disease results, along with a lack of preparedness for climate 'shocks' such as floods. Poor sanitation conditions are exacerbated by flooding, resulting in outbreaks of diseases such as cholera. Exposure to climate-driven disasters is thus a key climate-health link. Temperature and humidity are also linked to increased prevalence of tropical diseases such as malaria.

Malnutrition and food security-related diseases are common in the rural areas of southern Africa and projected climate change scenarios are likely to worsen this. For example, droughts have already resulted in low crop yields.

For southern Africa, peace is not just the absence of violence but other things that people are fighting for everyday ... food, health, struggle with HIV/AIDS. When livelihood situations are broken, that's when it is realised as a peace and security issue. Adaptation needs not only be sensitive to local resources, it needs to be conflict-sensitive.

Transboundary solutions and ecosystem-based management

Shared water resources in southern Africa support significant proportions of each state's economic production and social development. Cooperation is especially important in transboundary river basins as activities upstream have far-reaching impacts downstream and across borders. Water management and use within river basins – although an issue of multilateral interest – can develop either into cooperation, conflict or tension between states.

Millions of people across southern Africa depend directly and indirectly on ecosystem services for their food, water and energy security, as well as their health and livelihoods. In southern Africa, lessons from community-based management of forest, rangelands, wildlife, wetlands and their associated biodiversity show how ecosystems can contribute to reducing vulnerability and increasing resilience of local communities dependent on natural resources.

Adaptation strategies then, should include the role of ecosystems and natural resources in strengthening resilience for local communities. Ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) refers to the sustainable management, conservation, and restoration of ecosystems and their biodiversity to provide services that support adaptation, build resilience, and in so doing can generate significant socio-ecological, socio-economic and cultural benefits.

In southern Africa, change in land cover is a key driver to changes in ecosystems and their services. Climate change is likely to worsen this situation, further eroding livelihoods security.

Investing in natural capital is key to strengthening resilience of both ecosystem services and local communities in the face of climate change. Enhancing ecosystem resilience restores natural protection against extreme climatic events, thus limiting losses and damages due to climate variability and change. Financial payments, compensation or exchanges for conservation or restoration of vital ecosystem goods and services can be achieved through such schemes as Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES). Successful PES can be structured to provide an income buffer for communities dependent on natural resources, and can increase resilience in the face of climate shocks. Instead of physical infrastructure, PES can lead to investment in upstream watershed conservation and community adaptation to ensure sustained flow of water for downstream communities.

The establishment and development of peace parks is an approach to jointly manage natural resources across political boundaries. It is a good example of partnerships between governments and the private sector – it also contributes to confidence building among inter-country parties and can result in significant human security benefits if innovative ways to protect and advance livelihoods and rights of communities living along political boundaries are advanced.

- Kgalagadi – The first peace park, opened May 2000 (Botswana; South Africa)

- Lubombo – Includes five transfrontier conservation areas, established June 2000 (Mozambique; South Africa; Swaziland)

- Maloti-Drakensberg – Established June 2001 (Kingdom of Lesotho; South Africa)

- Great Limpopo – Established December 2002 (Mozambique; South Africa; Zimbabwe)

- /Ai/Ais-Richtersveld – Established August 2003 (Namibia; South Africa)

- Greater Mapungubwe – Opened September 2004 (Botswana; South Africa; Zimbabwe)

- Malawi/Zambia – Established April 2011 (Malawi; Zambia)

- Kavango-Zambezi – Treaty signed August 2011 (Angola; Botswana; Namibia; Zambia; Zimbabwe)

- Lower Zambezi-Mana Pools – In planning (Zambia; Zimbabwe)

- Liuwa Plain-Mussuma – In planning (Angola; Zambia)

Mozambique

Many communities of southern Africa are entirely dependent on natural resources and on remittances from migrant family members. They often lack basic services and alternative income generating activities to subsistence farming. Family members who stay behind when their husbands migrate sit outside their grain and livestock store in Canhane Village, Gaza Province. Water cans, seen in the background, are used to collect water from the dam. With climate change, the difficulties faced by family members, mostly women, will increase.

Mobility and migration

Southern Africa has experienced high-volume migrations for more than a century. Colonial era coerced inter-country migrations were a source of employment and income for the majority adapting to monetary economies with decreased access to land and natural resources. Migration is driven by environmental push factors such as poor soils and heavy rains that threaten agriculture and food security, and pull factors such as the perception that better economic opportunities exist in urban areas, areas better endowed with natural resources, or areas with more benign climates. Rapid increases in urban populations combined with dwindling job prospects make rural to urban migration an impractical adaptation strategy. Other forms of migration – urban to rural, rural to rural (already reported from some countries such as Zambia) – may be seen in future as increased poverty and climate change impacts on the urban poor.

It is not clear how human mobility trends will evolve with climate change but a number of scenarios are possible. The western parts of the sub-continent will get progressively warmer and drier while the eastern parts will get warmer and wetter, but with heavier, less frequent rainfall episodes. Both of these scenarios may cause agricultural, health and flooding problems, which may precipitate as yet unpredictable further migrations.

Climate change could lead to an erosion of livelihood sources for both migrants and hosts. Where access to and use of resources is further impacted on by migrants, conflicts are likely to result. In rural areas with water scarcity and poor soils, those who 'stay behind' (particularly women, children and the infirm) are likely to face increased hardships due to climate change. But those who move to urban areas are increasingly joining the multitudes of the urban poor, putting increased strain on already stretched local authorities that are struggling to provide adequate services such as water, energy and jobs.

Migration and climate change risks